Authentic Creativity in the Age of AI: Lessons from Johannes Itten

Intro

One of the most persistent questions for me has always been: “How is authentic creativity born?” Where do we find that inner source—untainted by trends and overexposure, free from the fear of critique or imperfect technique? I keep circling back to this question, again and again, and often bring it up in conversations with people from different creative fields.

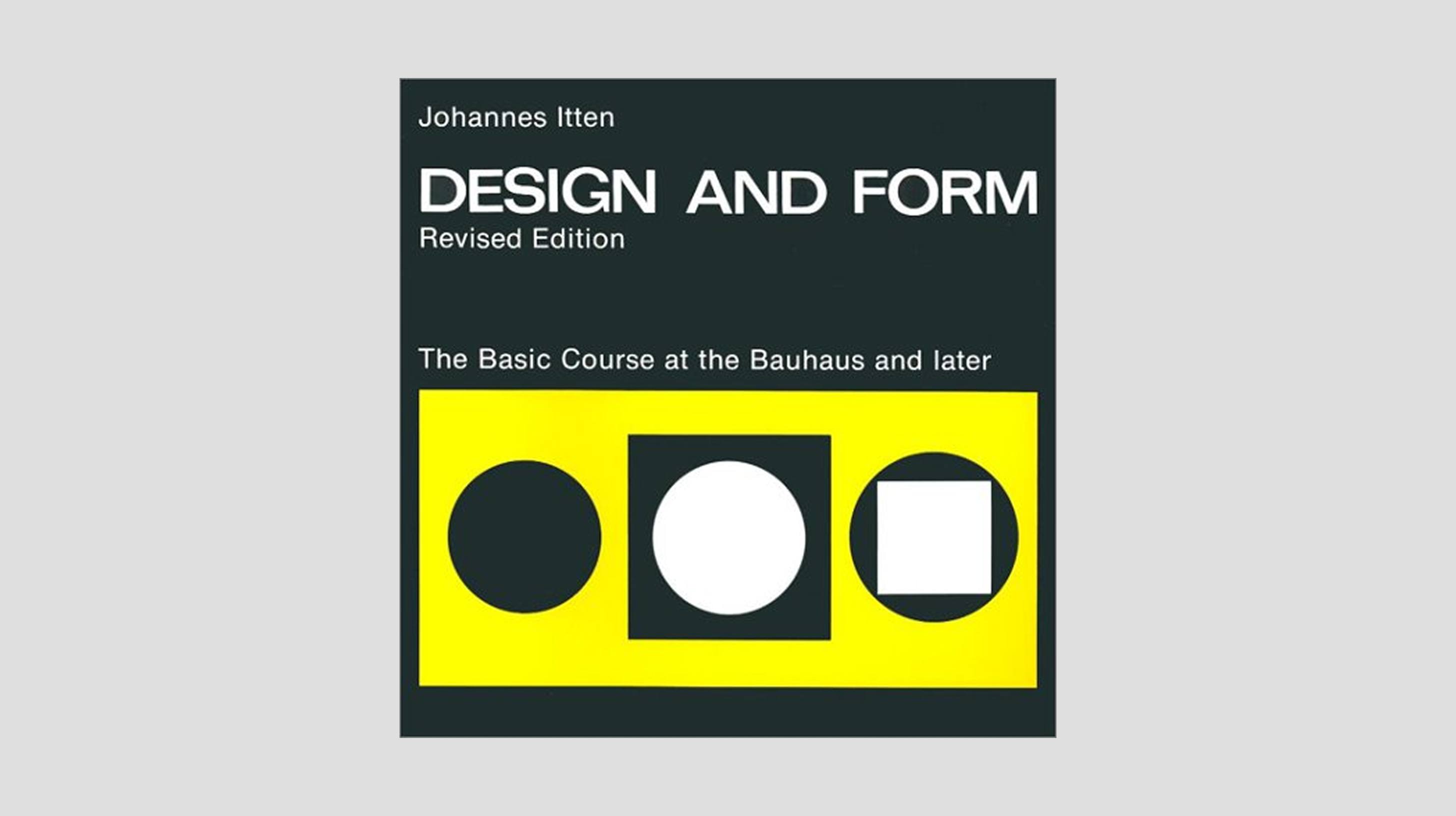

That’s why it was so unexpected to discover answers in a book where I thought I’d only find dry academic theory - “Design and Form. The Basic Course at the Bauhaus and Later” by Johannes Itten. Instead of rules, I encountered a philosophy that feels strikingly modern. I still can’t believe how innovative Johannes Itten was, one of the very first Bauhaus teachers.

This book set off a long chain of reflections in me—about the education system, about my own path, and even about regrets. How essential it is to meet “your” teacher—the one who helps you uncover not just technique, but your inner voice.

In this article, I shared the moments that resonated most deeply: Itten’s teaching methods and how, even in the age of algorithms, it’s still possible to nurture originality of thought. He wasn't teaching design - he was teaching how to be while designing.

Johannes Itten taught at the Bauhaus from 1919 to 1923. His approach was eventually considered too mystical, too subjective, too focused on individual development rather than universal principles. He was, in many ways, the school's heretic. Which might be exactly why his ideas feel so necessary right now.

The Instrument You Already Have

Itten believed creative work starts in the body. Before his students touched a brush, he had them release tension from their shoulders, soften their grip, breathe. His question was simple and kind of devastating: how can a clenched hand draw freedom?

He used movement, breath work, even vocal exercises to help students find where creative energy actually comes from. "The way we breathe is the way we think," he wrote, "the way we build the rhythm of our daily activity."

It's practical. We've gotten used to thinking about design as a mental thing executed by hands. Itten reminds us there's a whole breathing, sensing body between thought and mark.

The irony isn't lost on me: we can now generate designs without moving our bodies at all just type prompts while slouched in our desk chairs, so Itten's insistence on embodied practice feels both ancient and strangely revolutionary.

Learning Through the Senses

Itten's teaching had a specific order: feel > understand > do.

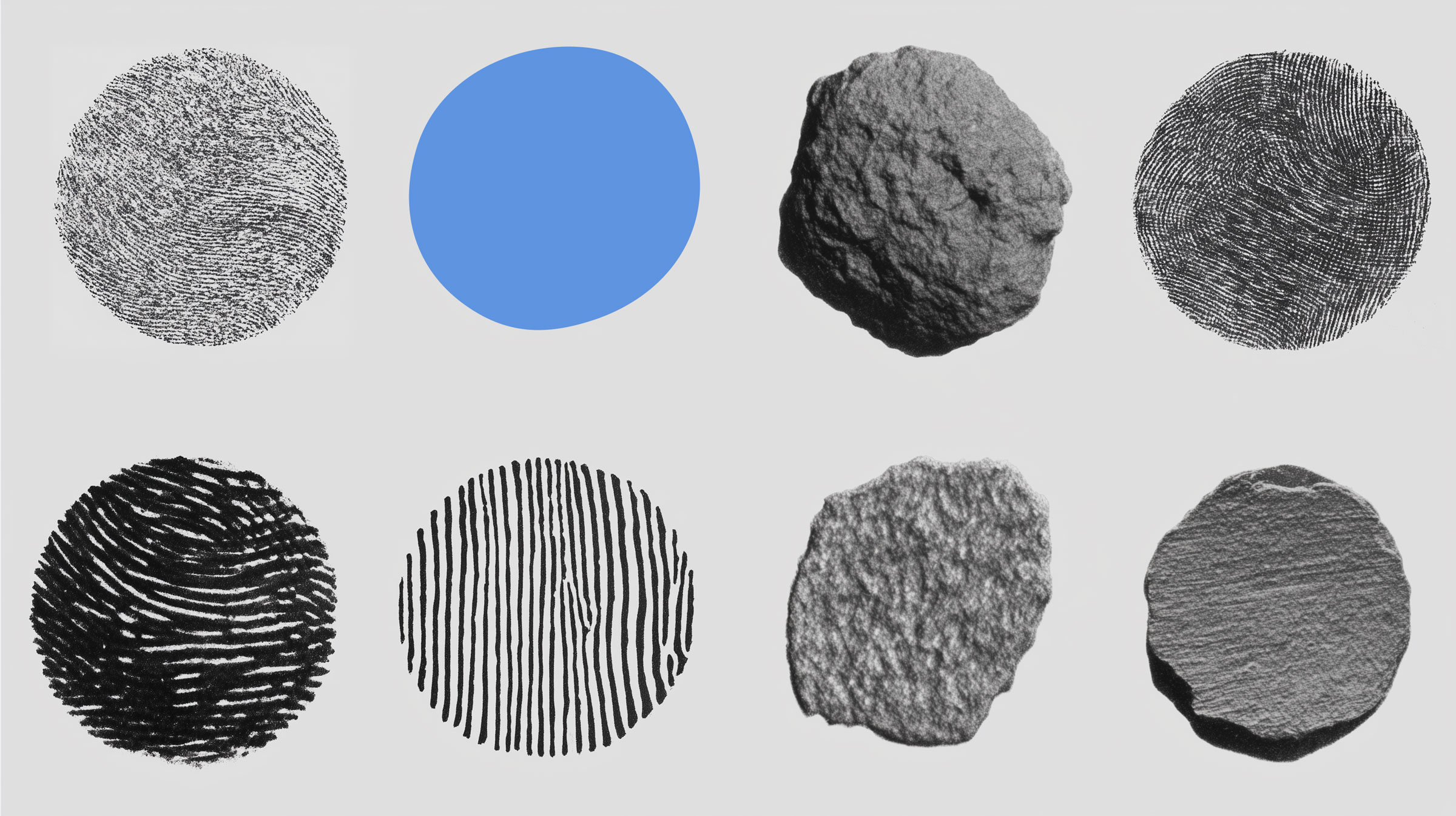

He'd have students explore materials blindfolded. Rough bark, smooth river stones, wool, glass, feathers, metal shavings. They'd build contrasts through touch alone, making compositions based purely on how things felt. These weren't exercises in technique - they were about attention, about getting back that sense of discovery we had as kids when we first touched different textures.

In an age of instant visual reference, this feels radical. When's the last time any of us designed something without immediately pulling up references, precedents, Pinterest boards? We've trained ourselves to think visually first, to scroll through thousands of images before we've held a single actual object.

AI can show us infinite images of texture. It can render bark with photorealistic precision. But it can't teach us what it actually feels like to run your fingers across that bark, to feel the catch and release as you trace its grooves. That knowledge changes what you make.

The Irreducible Self

What really got me about Itten was his reverence for subjectivity. In an educational environment obsessed with universal principles and objective truths the Bauhaus was literally trying to discover the grammar of modernity - Itten took a completely different stance.

He observed that "simple people, unspoiled by school, almost always work with form and color subjectively," and he meant it as high praise. He studied children's drawings not to correct them but to understand what gets lost when we "educate" that subjectivity away. He had students draw the same object over and over, not to improve their technique but to discover their particular way of seeing.

For Itten, a teacher's job wasn't to correct everyone toward some ideal, it was to protect each student's particular way of seeing. Subjectivity wasn't a bug to fix. It was the whole point.

He wrote about how ten students in a room would draw ten different circles. Each circle would reveal something about the person who drew it—their temperament, their rhythm, their particular nervous system. Instead of drilling them all toward a "correct" circle, Itten would have them study their own circles, become conscious of their tendencies, then work with those tendencies instead of against them.

This hits differently now. When AI can produce technically perfect work in any style, when it can generate a flawless circle or mimic any designer's aesthetic with creepy accuracy - what becomes valuable? Maybe exactly that irreducible human skew. The specific gravity of one person's perception. The circle that could only come from your hand, your breath, your particular way of existing in space.

The Rhythm You Can't Teach

One of Itten's weirdest exercises had students speed up their handwriting. They'd write a sentence, then write it faster, then even faster, until the letters started dissolving. What remained wasn't language but gesture - pure rhythm made visible.

He compared this to breathing, to tides, to heartbeat. Something alive that resists full explanation. Each student's gesture was unique, he said, like a signature written by the body itself.

Try it yourself right now. Write your name slowly, carefully. Now write it as fast as you possibly can. Look at the second version. See how it reveals something the first one hides? A quality of movement, an essential rhythm that belongs only to you.

Itten believed this rhythm was foundational. It couldn't be taught, only discovered. And once you found it, it should inform everything: the pace of your work, the proportions you choose, the spacing, the intervals. Your work should breathe at your speed.

AI can analyze rhythm, even replicate it. Feed it enough of your work and it can spit out convincing approximations of your timing, your spacing, your particular intervals. But it can't have a rhythm. Its variations are calculated, algorithmic. Ours come from the fact that we're biological, that we get tired and get energy, that our attention drifts and sharpens with hunger, mood, the quality of light, the argument we had that morning.

Work that comes from authentic rhythm has a quality call it life, coherence, or just "feeling right" that's hard to name but immediately recognizable. You can sense when something's been made by a nervous system in sync with itself.

The Silence Between Marks

Itten wrote about what happens in the pause before making a mark. That moment of potential where the work exists in your imagination but not yet in material form. He called it the "immaterial" realm and thought it was just as important as the actual outcome.

This waiting, this receptive silence, was part of the practice. Students learned to feel the difference between the urge to make something and actual readiness to make it. To sense when the image had fully formed internally before committing it to external form.

It's a kind of listening.

In my own practice, I've started noticing this more. There's a difference between generating rapidly—trying option after option, clicking through variations—and that rarer state where you're waiting for something to clarify. In the first mode, you're often just running from uncertainty. In the second, you're inhabiting it, letting it teach you what wants to emerge.

AI collapses the gap between impulse and output. Thought becomes image in seconds. There's obvious power in that immediacy. But something gets lost too: the slow formation that happens in uncertainty, the way an idea transforms as it gestates, the discoveries that only come when you're forced to live with a problem before solving it.

Itten's students spent weeks on single exercises. Not because they were slow—it's because the whole point was duration, the transformation that only happens through sustained attention over time.

The Practice of Attention

Itten describes an exercise that sounds almost ridiculous: students spent an entire month drawing a single object. Not from every angle, not in every medium. Just one object, from one view, over and over.

The point wasn't to perfect the drawing. The point was to keep looking. To discover that familiarity doesn't mean you've actually seen everything. That attention can deepen infinitely.

By week two, students would see details they'd missed. By week three, they'd notice how the object looked different in morning light versus afternoon. By week four, they'd realize they weren't drawing the object anymore—they were drawing their evolving relationship with the object. Each drawing was a record of their attention at a particular moment.

This practice feels almost impossible to imagine now. We're trained for rapid cycling—scroll, swipe, next, refresh. The idea of staying with one thing for a month seems not just boring but somehow professionally irresponsible. Shouldn't we be exploring more? Generating more? Staying current with more?

But Itten knew something we keep forgetting: depth and speed are inversely related. The cost of seeing everything quickly is seeing nothing deeply. And depth is where the interesting stuff lives—the nuance, the paradox, the things that don't reduce to a formula.

AI accelerates everything. It can generate a hundred variations in the time it takes you to sketch one. That speed is useful—I use it constantly. But it's worth noticing what we lose: the discoveries that only come from sustained, focused attention. The understanding that emerges not from seeing many things but from truly seeing one thing.

What Remains Human

Reading Itten while living with generative AI, I keep coming back to one question: what can't be synthesized?

Maybe it's this: the experience of being in a body while making something. The sensation of material resistance. The wobble of subjective perception. The breathing silence between decisions. The specific rhythm that emerges from your particular nervous system encountering the world.

Itten quoted Laozi: "The material is useful, the immaterial is the essence of being."

Generative tools are going to become infrastructure, like electricity. They'll handle the material layer brilliantly—the production, the variation, the technical execution. But the immaterial—the quality of attention, the rhythm born from breath, the subjective form that can only come from your particular way of being—this stays unreproducible.

Not because AI can't approximate it. With enough of your work, it probably can. But because approximation isn't origin. A photograph of fire isn't fire. A recording of a voice isn't the voice itself, emerging from a throat, shaped by a particular mouth, carrying the memory of everything that person has ever said.

The Real Work

I've been thinking about what it means to be a designer when design can be generated. What's left as our work, our value, our contribution?

Itten's answer, I think, is this: cultivation. Not of style—style can be copied. Not of technique—technique can be learned or automated. But cultivation of your particular way of perceiving and responding to the world.

This means practices that might seem completely unrelated to "getting better" at design:

- Learning to recognize when you're tense versus when you're open

- Discovering your natural rhythm instead of fighting it

- Developing sensory intelligence through direct contact with materials

- Protecting your subjective response instead of defaulting to what everyone else thinks

- Practicing sustained attention in an age of distraction

- Sitting with uncertainty instead of rushing to solution

Maybe the real work now isn't competing with what AI generates effortlessly, but cultivating what only comes from being human and awake. From having a body that gets tired, senses that can be sharpened, attention that can deepen, and a way of moving through the world that belongs only to you.

Itten's insight was that creativity isn't about applying techniques to problems. It flows from a particular quality of being—alert, embodied, subjectively engaged—that meets the world with all its resistance and surprise.

The machines will keep getting better. They're already incredible. But they'll never have our problem: the problem of being conscious in a body, of hunger and fatigue, of memory and forgetting, of moods that shift like weather, of perceiving the world through this specific nervous system at this specific moment in time.

That problem, it turns out, is also our advantage. It's the source of everything unrepeatable, everything that emerges from being alive.

Maybe that's what we're really making: not designed objects, but records of what it felt like to be awake and paying attention. Evidence that someone was here, breathing, sensing, responding to what called to them.

That's the work. That's what stays human.

In writing this, I've tried to capture how Johannes Itten helped his students discover their true selves in creativity—through bodily practices, breathing, attention to rhythm, and intuition. He opened the door to that space where authentic expression is born, beyond mere technical skill. Today, in the age of synthetic content, this approach feels almost radical: algorithms don't teach us how to be ourselves, they teach us how to replicate the average.

And this raises a troubling question: is generative content becoming the new norm where originality loses its value? If society begins to settle for the visual "average," we risk living in a world where a unique voice is treated as noise, and speed and convenience matter more than meaning. Can authenticity survive this crisis? Or are we heading toward a new aesthetic where originality becomes rare—a kind of luxury reserved only for those willing to resist mass standardization?

Perhaps the answer lies not in rejecting the tools, but in returning to Itten's fundamental insight: that authentic creativity springs from the irreducible fact of being yourself, in a body, paying attention. The algorithms will keep improving, but they can never replace the work of becoming more fully who you are. That work—uncomfortable, slow, impossible to shortcut—might be the only thing worth doing.